Remembering my father:

None of this makes any sense as I rock back and forth in the mostly dark with Sprout on my chest. Bean, up in his bunk bed is humming along with me as I pick up a tune and begin to sing and then I realize: I'm singing the song I sang to him over and over as he lay dying. I'd sit there for hours beside his bed, watching the shadows cast by the dancing leaves of the cherry tree on the pale yellow wall.

The song is an old Gaelic blessing. I learned it in school as a child, at the end of my fourth grade year before all of us were released for the summer to climb trees and run wild. By then I lived in a tract home in the Northridge hills. There was an olive tree that spread over the front driveway, and the driveway would get stained by the dark purple fruit that would also stain our feet when we ran on it barefoot. In the backyard we had a redwood hottub that my parents could never afford to heat, but in the summer we filled it anyway and lolled about ducking to the bottom and popping back up, the water running in rivulets off our cheeks and eyelashes.

What I remember about my father from that time was his office that was separated from the house by a workshop. It had sliding glass doors that opened on to the back patio, and you could reach it by either going through the workshop, picking your way through pipe clamps and table saws, or from that sliding door. I remember watching him at work through that door, his back to me as I'd swing on the swing he'd hung from the patio veranda. It was something I did a lot, growing up: Watch his back as he worked on his computer.

My boys will likely have a similar memory of me.

"Shush, Mommy's working."

I try to sit at the dining room table and let their busy world spin around me, but like my father, I crave the silence of uninterruption; the solitude of that comes with focus.

Now I'm rocking in the tender dark of my son's bedroom. Sprout's limbs are already lanky in my lap. He's three; the years are galloping.

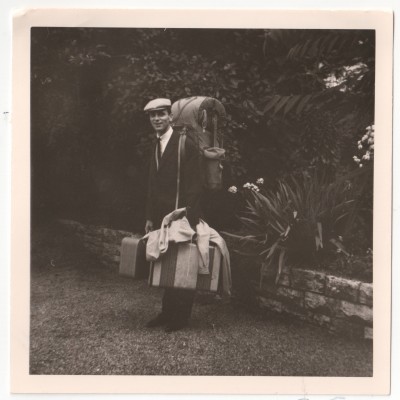

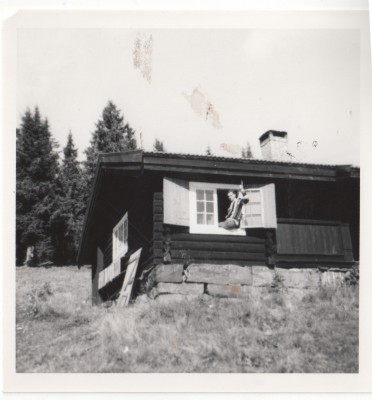

After I tuck him in and rub noses with both boys and kiss their cheeks, I search for a box at the back of a closet: With photo albums in it from a decade before I was born. I sift through the pictures of my father then; wondering what he must have been like in that alternate lifetime before I was even an inkling in it.

This is just it, this life: An inkling, a hundred inklings, and then blink.