Trying for fire

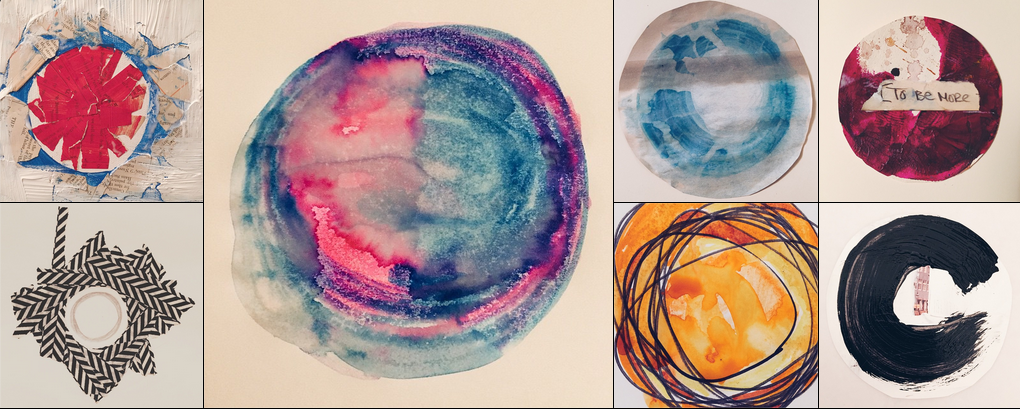

I should be doing other things. There is a list. Deadlines. So many shoulds. Instead I am thinking about the rose that my youngest picked today that smelled like euphoria, and of his smile asking to play catch, and of the homeless people I pass by again and again, each time feeling everything and still not knowing how I can help, passing as I do in my car without carrying cash, or on the sidewalk with my dog. Instead I've got headphones in my ears, and paint on my fingers, and I'm circling my circles, and I've got this Tim Seibles poem on mind.

I should be doing other things. There is a list. Deadlines. So many shoulds. Instead I am thinking about the rose that my youngest picked today that smelled like euphoria, and of his smile asking to play catch, and of the homeless people I pass by again and again, each time feeling everything and still not knowing how I can help, passing as I do in my car without carrying cash, or on the sidewalk with my dog. Instead I've got headphones in my ears, and paint on my fingers, and I'm circling my circles, and I've got this Tim Seibles poem on mind.

TRYING FOR FIRE

Right now, even if a muscular woman wanted to teach me the power of her skin I'd probably just stand here with my hands jammed in my pockets. Tonight I'm feeling weak as water, watching the wind bandage the moon. That's how it is tonight: sky like tar, thin gauzy clouds, a couple lame stars. A car rips by -- the driver's cigarette pinwheels past the dog I saw hit this afternoon. One second he was trotting along With his wet nose tasting the air, next thing I know he's off the curb, a car swerves and, bam, it's over. For an instant, he didn't seem to understand he was dying -- he lifted his head as if he might still reach the dark-green trash bags half-open on the other side of the street.

I wish someone could tell me how to live in the city. My friends just shake their heads and shrug. I can't go to church--I'm embarrassed by things preachers say we should believe. I would talk to my wife, but she's worried about the house. Whenever she listens she hears the shingles giving in to the rain. If I read the paper I start believing some stranger has got my name in his pocket on a matchbook next to his knife.

When I was twelve I'd take out the trash-- the garage would open like some ogre's cave while just above my head the Monday Night Movie stepped out of the television, and my parents leaned back in their chairs. I can still hear my father's voice coming through the floor, "Boy, make sure you don't make a mess down there." I remember the red-brick caterpillar of row houses on Belfield Avenue and, not much higher than the rooftops, the moon, soft and pale as a nun's thigh. I had a plan back then--my feet were made for football: each toe had the heart of a different animal, so I ran ten ways at once. I knew I'd play pro, and live with my best friend, and when Vanessa let us pull up her sweater those deep-brown balloony mounds made me believe in a world where eventually you could touch whatever you didn't understand.

If I was afraid of anything it was my bedroom when my parents made me turn out the light: that knocking noise that kept coming through the walls, the shadow shapes by the bookshelf, the feeling that something was always there just waiting for me to close my eyes. But only sleep would get me, and I'd wake up running for my bike, my life jingling like a little bell in the breeze. I understood so little that I understood it all, and I still know what it meant to be one of the boys who had never kissed a girl.

I never did play pro football. I never got to do my mad-horse, mountain goat, happy-wolf dance for the blaring fans in the Astro Dome. I never snagged a one-hander over the middle against Green Bay and stole my snaky way down the sideline for the game-breaking six.

And now, the city is crouched like a mugger behind me--right outside, in the alley behind my door, a man stabbed this guy for his wallet, and sometimes I see this four-year-old with his face all bruised, his father holding his hand like a vise. When I turn on the radio the music is just like the news. So, what should I do--close my eyes and hope whatever's out there will just let me sleep? I won't sleep tonight. I'll stay near my TV and watch the police get everybody.

Across the street a woman is letting her phone ring. I see her in the kitchen stirring something on the stove. Farther off a small do chips the quiet with his bark. Above me the moon looks like a nickel in a murky little creek. This is the same moon that saw me twelve, without a single bill to pay, zinging soup can tops into the dark -- I called them flying saucers. This is the same white light that touched dinosaurs, that found the first people trying for fire.

It must have been very good, that moment when wood smoke turned to flickering, when they believed night was broken once and for all -- I wonder what almost-words were spoken. I wonder how long before that first flame went out.

First published in Hurdy-Gurdy by Tim Siebles